The Johannesburg High Court has given Parliament two years to ‘cure the defects’ in the Basic Conditions of Employment Act and the Unemployment Insurance Fund (UIF) Act.

The court declared sections of these acts unconstitutional for unfairly discriminating against mothers and fathers, surrogate and adoptive parents when it comes to ‘maternity leave’. Printing SA recently held a webinar about the groundbreaking new order, which was was conducted by Michelle Naidoo, partner at Mooney Ford Attorneys.

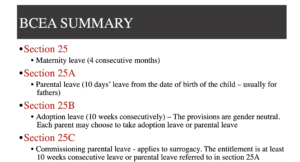

Naidoo took attendees through current basic conditions of the employment act in terms of maternity and paternity leave. A basic summary can be seen below:

Naidoo added that it is also voluntary for an employer to offer additional leave. Prior to 2020, fathers were strictly only entitled to family responsibility leave, which is three days for the birth of a child.

That was amended in 2020 to entitle fathers to ten consecutive days of leave. The pay for fathers is also, once again, governed by the UIF legislation. An ordinary UIF claim would be made, and in the event that fathers wanted to take additional periods of leave, they would have to arrange with their employer to take that leave from their ordinary annual leave entitlements. Sometimes fathers even take unpaid leave in the event they wish to spend more time with their newborns.

‘We then had our legislation introduce adoption leave at the same time, because once again, adoption leave wasn’t provided for under our legislation. That granted adoptive parents 10 consecutive weeks of leave to spend with their adopted child, which could have been a newborn or a young child. So, that was introduced again in 2020. The interesting thing about the adoption leave is that, if it’s two parents that have adopted a child, they can share two kinds of leave,’ said Naidoo. ‘They can either say one parent is going to take the full benefit of adoption leave, and the other parent will take parental leave, which is the ten consecutive days. So both parents get to elect which one of these entitlements they would elect to share between them.’

‘We then had something very new, which is commissioning parentally, and this applies to surrogate motherhood circumstances. Where there’s a surrogate motherhood agreement, which is reached between parties, the surrogate mother would then become entitled to this leave, which is commissioning parental leave. That one is also 10 consecutive weeks, and for this leave as well, the commissioning mother and father of the surrogate child can decide to share the 10 consecutive weeks and elect which one is going to take the parental leave option of 10 days, and which of the two will take the 10 weeks commissioning leave entitlement.’

‘Again, this is covered by our UIF legislation. It’s not compulsory for employers to be responsible for payment during this period, but technically it’s a responsibility and obligation on employers to do everything that is necessary to assist employees in their claims for these benefits under the UIF Fund.’

Naidoo said employers should make sure that they have all of these items covered in their parental leave policy. It’s very important to ensure that they have procedures in place to manage these situations as they arise.

Van Wyk And Others Versus Minister Of Employment And Labour

This case deals with a married couple, Werner and Ika Van Wyk, who had a child, and who were essentially the first and second applicants in the case. The further applicants in the matter are gender and equality groups that supported these two individuals to take up this matter and to challenge biased provisions in the basic conditions of employment, or discriminatory provisions in the basic conditions of employment, which favour mothers instead of fathers in the situation of granting parental leave benefits.

The main respondent in the case was the Minister of Labour, because the minister is the custodian of employment and labour laws in the country and would’ve been responsible for the current framework of parental leave benefits as per the Basic Conditions of Employment Act.

The main challenge that was raised in the matter by the applicants was that there’s an unequal burden on the mother being the primary caregiver under South African legislation, and there are real parenting challenges that the primary caregiver has to endure in the early phases of a child’s development.

It was recognised that to be a primary caregiver involves significant work and resilience, as well as the exhaustion and sacrifice that the primary caregiver has to go through during that period. The framework of our legislation presumes to put all of that significant work and extreme conditions on one party – the mother, and it was argued that this is unfair.

The applicants in this case also argued that placing all the emphasis on the mother constitutes unfair discrimination. It’s a double edged sword, unfair discrimination, assigning the primary caregiver role on a mother, which could potentially impair her dignity. But on the other hand, it’s also denying equal recognition of the father, in terms of being a caregiver. These are two very specific and valid arguments that were raised.

There’s a modernisation of the family model. More women are working, and more women are becoming breadwinners in homes due to circumstances and the economy, etc. This is what the Van Wyk’s experienced. Mr Van Wyk is a salaried employee, while Mrs Van Wyk is running her own business.

It was argued that Mrs Van Wyk could not afford to take four months of maternity leave, because she’s running her own business and needs to get back to work as soon as possible. There’s not going to be a subsidy of her salary, because if she’s not working, then there is no income from her side of the business.

The only money that would be subsidised is UIF benefits. But in her instance as a business owner, she wouldn’t even be entitled to claim because she’s not working as an employee. The couple was in a predicament. On the other hand, Mr Van Wyk would be more suitable, in terms of their family model, to be granted time off.

The idea was that Mrs Van Wyk would spend some time being the primary caregiver, and that would be potentially one to two months after the birth of the child. But for the remaining period, essentially the ideal situation for that family is for her to return to work, and then for Mr Van Wyk to become the primary caregiver.

‘I know this will resonate with many of us because many of our families over time have changed to this more modern sort of structure, and many more people are opening their own businesses and exploring these kind of opportunities, as opposed to the traditional employment model.’

‘So essentially what was argued in the case from a legal point of view is that the framework is breaching section 9 of the Constitution, which says that everyone is equal before the law and has the right to equal protection and benefit of the law.’

‘Fathers in South Africa were not being treated equally in terms of our basic conditions, our entitlements, and the discrepancy between the entitlements for maternity leave and parental leave, etc. Essentially, there was a call for reform by the applicants in the matter.’

The court found that these provisions of the Basic Conditions of Employment Act, as well as the UIF legislation related to these provisions of maternity, paternity, adoptive, and commissioning leave benefits, unfairly discriminated between mothers and fathers.

The court granted the applicants the relief that they sought in this matter, declaring those provisions unconstitutional. Whenever a court declares any legislation unconstitutional, they would in the ordinary course give the legislature some time to rectify those provisions.

‘The order that was sought by the applicants in this matter was for the court to allow the Minister of Labour two years to do what is necessary to to fix these provisions, which unnecessarily discriminate between mothers and fathers. In fact, in the judgements, the court said that Parliament must get to work to eliminate these inequalities. So, by those words, it’s implied that that new legislation may very well be introduced as early as next year in relation to this. The court also expressed a view of the appropriate immediate means by which to remove inequality. The court said all parents should enjoy four months of parental leave collectively.’

How Does This Affect Employers?

‘Be aware that this change is coming. Please ensure that you start looking at your maternity and parental leave policies. Also bear in mind that many employers do offer enhanced benefits. You may want to consider what your organisation can afford or can offer as enhanced benefits. But obviously that’s entirely voluntary and it’s up to every company’s economical and operational situation. Look at that and get ready to implement policies and procedures which are going to regulate this.’

Parental Leave In Other Countries

‘Many countries in the world have implemented sharing of parental leave for some time. In Sweden, mothers are given 240 days, and fathers get 240 days. It’s 16 months, essentially, in total for parents. They also have transferable parental leave of 150 days. So either the father or the mother can transfer 150 days to the other, dependent on what is going to work for them in terms of being the primary caregiver. They are a very wealthy country so the payment during this period for mothers and fathers is 80 percent of the parents’ usual pay.’

‘In Finland for example, it is 164 days each, and the transferable portion is 69 days and 70% of the employee salary is covered. In Bulgaria it’s 410 days for maternity leave. Paternity leave is 15 days. And again, there’s a transferable portion, it’s variable – a mother can elect to transfer any portion of her maternity leave entitlement after a period of six months.’

‘Maternity and parental leave between parents is not something which is completely new from a global perspective, and various countries have adopted these approaches. I think it’s the correct approach. Parents should be allowed to decide among themselves who will be the primary caregiver and who will do what portion of the leave period,’ concluded Naidoo.

PRINTING SA

+27 11 287 1160

info@printingsa.org

http://www.printingsa.org